With this post, I’ll share some thoughts arising from my last trip in Eastern Europe. Outside major cities, I almost always felt I was the only westerner in town (which was good…), and communicating was not easy, given the language barrier and the unfamiliarity with foreigners in these countries.

While the Czech Republic has been welcoming and relatively friendly, Slovakia seemed to me an “autistic nation”. Nobody there showed any empathy at all. I don’t know if as a result of the economic crisis or of the Soviet legacy, but I have never felt so uncomfortable while traveling in Europe.

Yet we share the same currency, which once meant being brothers. I think that Slovaks should travel more. We may institute a European passport, requiring all citizens of the Union to visit other member states. A year dedicated to traveling and spending time abroad, in order to recognize and respect each other.

But the country that most piqued my interest is certainly Hungary. Perhaps influenced by “Cemetery of Splendour” by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, which I’d seen the night before leaving, the past in Hungary seemed ubiquitous, highly visible, almost eerie, just like the two goddesses of the movie, sitting quietly at the table with the main character and thanking her for the beautiful gifts.

This magical atmosphere, where the present time is compressed by the legacy of the past, has nothing to do with monuments and churches. It’s linked instead to the sense of abandonment and decadence in everyday’s life, to railway stations left untouched from before the fall of the wall, to wild gardens, to playgrounds and houses with no sign of life. And you won’t find this in tourist maps.

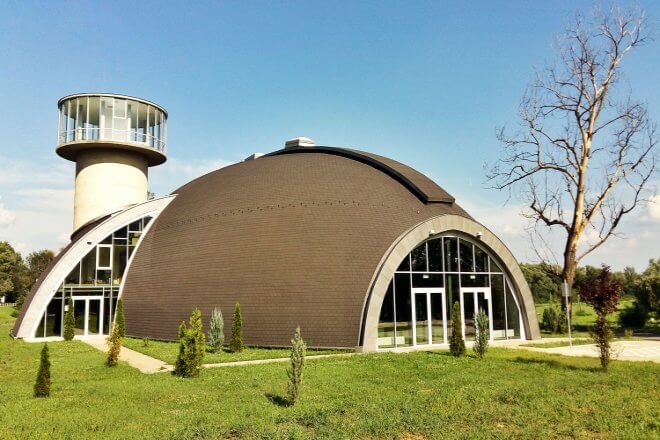

The overlap of architectural layers in Hungary is really impressive, with ancient medieval walls, typical country houses, soviet-era structures, and hyper-modern buildings seeking an impossible dialogue. But in this enigmatic and often surreal patchwork of styles, the real protagonist is nature, which is always regaining its spaces, piece by piece. The aesthetics and poetry of Béla Tarr is recognizable on every corner, enlightening a bleak reality, the result of men’s powerlessness.

In Hungary, to find out if a place is inhabited you have to go very close to it, and most of the time that’s not enough. At the foot of the Tokaj Bridge, shortly after a futuristic building of dubious value (financed by the EU), and among countless abandoned campsites and holiday cottages, I was fascinated by this house.

Looks like the owners were kidnapped by aliens a few years ago and everything has remained as it was, in the total indifference of the rare people passing by. Gustave Flaubert said: “Travel makes one modest. You see what a tiny place you occupy in the world.” Well, in Hungary one feels completely insignificant. The passage of time is an independent process, on which we should not interfere.

In Hungary, no one speaks English and you’re often forced to eat goulash since it’s the only recognizable word in the menus. Most of all, I will miss my weird conversations with the locals. I remember one in particular, at Miskolc railway station. I was just wondering which train I had to take, given that two identical ones were arriving at the same time, but from opposite directions.

An old man, after giving me a hint, continued to talk amiably in Hungarian for another ten minutes, until his granddaughter stopped him to say something like: “why do you keep talking to this guy, who does not understand a single word of our language?” I was tempted to ask her, in any language, to let him go on. We’ve always been saying the same old things because we have the exact same needs. Language is not that important when there are empathy and mutual respect.